📚 The Comfort of Fictional Religions: The Spark

Nightcrawler’s philosophy for an ever-changing people.

This is an entry in The Good Books. Be sure to check out the other posts in this series on Bokononism, sensayers, the Monk & Robot books, and Earthseed. If you are able, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

I love high-concept sci-fi, and for the last several years my favorite sci-fi has been happening in Marvel’s X-Men line of comics. In 2019, Jonathan Hickman rebooted the franchise with interlocking series, House of X and Powers of X (pronounced “House of Ex, Powers of Ten” and colloquially called HoxPox).

The reboot kicks off with some big changes:

Mutants have established their own island country called Krakoa,

They have created life-saving medicines they will give to the human populace in exchange for recognizing their country’s sovereignty,

They have defeated death by combining various mutant powers that backup a person’s psyche and recreating clone bodies—a reliable form of resurrection.

They announce these changes (except for defeating death; that is a closely-guarded secret) in dramatic fashion, sending a telepathic message to the entire world that “while you slept, the world changed.” They offer amnesty to all mutants, and that brings some prior villains into the fold. From the very beginning, these drastic changes bring about a long-standing conflict between mutants, baseline humans, and machines (this is Marvel, and there are several android-type entities that have gained sentience—including the Sentinels, long-time X-Men foes).

I think the Krakoan Era of the X-Books have worked so well is that from the beginning, Hickman established a writers room and allowed other writers to work in the vast sandbox he built. The parameters were wide enough that it enabled all sorts of stories: mystical stories in books like Excalibur, black-ops stories of protecting their new nation-state in X-Force, superhero stories in X-Men, space-faring stories in New Mutants, political stories in X-Corp, and so on.

Further, the cumulative ideas underlying the concept were so novel that writers & artists were able to put these decades-old characters through their paces and push them to change. This is no small feat in “Big Two” comics (Marvel & DC), where the illusion of change is part & parcel of the whole endeavor. And it is wholly appropriate for a franchise whose key feature is mutation.

One of my favorite stories, which has worked its way across multiple books, centers on Nightcrawler. Like most characters who’ve been around nearly 50 years (he debuted in 1975), he has a convoluted backstory. The son of a demon & a mutant with stereotypically-demonic physical features, he has been consistently portrayed as a theologically-curious and philosophically-inclined character. In fact, he was at one point a Catholic priest, though that story has been retconned.1

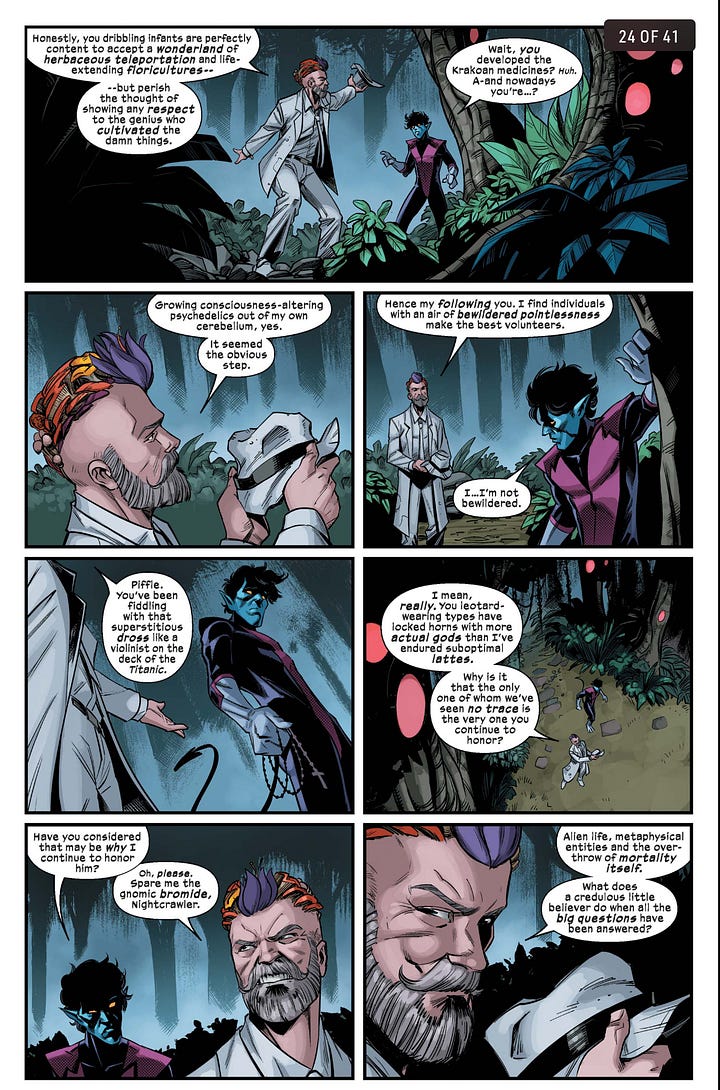

At the start of the Krakoan Era, Nightcrawler (aka Kurt Wagner) begins exploring the need for a new religious or spiritual practice for a new state. In the first issue of theWay of X series, author Si Spurrier & artists Robert Quinn (pencils/inks), Javier Tataglia (colors), and Clayton Cowles (letters) show what’s at stake: Nightcrawler goes on a mission with young mutants who do not fear death, he witnesses a ritual known as the Crucible in which depowered mutants are killed in ritual battle and are resurrected with their powers restored, and a super-scientist named Dr. Nemesis challenges him on what faith means in his changed world:

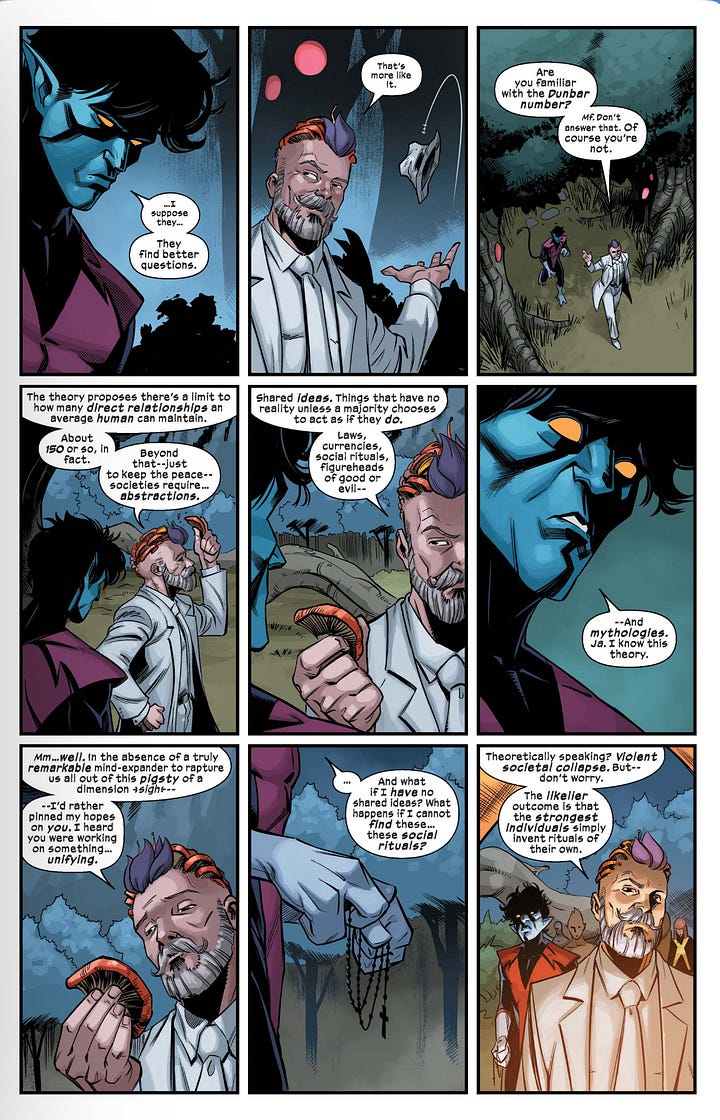

Dr Nemesis: “Alien life, metaphysical entities and the overthrow of mortality itself. What does a credulous little believer do when all the big questions have been answered?”

Nightcrawler: “…I suppose they…they find better questions.”

Dr. Nemesis: “That’s more like it.”

Confronted with this reality, Nightcrawler sets aside the idea of finding a unified belief, and pursues a new way of life.

This journey takes many twists and turns. As is common in contemporary comics, The Way of X paved the way for another book called Legion of X, which features the character Legion, Professor X’s son, who has all-powerful dissociative identities—a helluva metaphor for mental illness, among other things.

Throughout Legion’s publication history, he has gone from an out-of-control threat to a character with profound self-awareness. Throughout both Way and Legion of X, Legion and Nightcrawler serve as supporting characters for one another.

Eventually, Nightcrawler discovers his new philosophy he wishes to share with his fellow mutants, a people defined most essentially by their capacity for change. He calls it The Spark:

“This is not a mutant religion.

This is a way of living. Of loving and expressing and fighting and being. It moves us to adapt without restraint. It does not require prayer nor veneration. It does not demand that you put away your old gods. The spark is not jealous.

The spark is innovation and risk and mischief and courage.

If we allow it to guide us -- if we invite it to inspire our thoughts and actions -- I truly believe it will save us. The spark is anathema to meaninglessness.

The spark is creative. The spark is patient. The spark is bright and beautiful, despite having no form or mind. In truth, the spark is barely real at all. The spark is just an idea.

And yet?

The spark will burn to ash anyone who $*&$ with the right of mutants to pursue happiness.”

There is something beautiful captured here. A spark is small, but can spread—not unlike a mustard seed. A spark is bright, and should not hide under a bushel. A spark is warm, but its warmth fades in a moment if it is not fed and tended to.

I love that, within the context of the story, Nightcrawler fashions this philosophy out of his own experiences of faith and doubt and all the points of life between those two binaries. He is Catholic, yes; he is the son of a demon, yes; he is a mutant, yes; he is himself, yes.

The gift that these fictional religions give us is that we can see our own experiences mirrored in them without all the associations with our faith of origin (this is also the gift of fiction overall). Wrap it in something fantastical like being the mutant superhero Catholic priest son of a demon, and suddenly the multitudes of our own experience don’t seem so far-fetched.

Yes, these comics also rule because they are fun superhero shenanigans, and honestly there is more to the stories of Nightcrawler & Legion.

But if this has sparked your interest, go read them for yourself.2

For the non-nerdy, ‘retconned’ means “retroactive continuity,” where a writer/artist retroactively changes a story developed by a prior writer/artist.

Pun absolutely intended.