The importance of emotional work.

`As I continue to go through what I consider a “fallow” creative period—one where I work on things privately instead of regularly publishing essays or podcasts—I’ve been thinking about the inherent value of emotional work.

In light of everything we’ve experienced in the last year since society has sought to reckon with the pandemic, racial justice, and Christian extremism, it still surprises me how much value we put into our notions of “productivity.”

I’m guilty of this, too. I develop a nagging feeling in my mind when I get pulled down deep into my emotions by some turn of events—either in my personal life, or in the life of our country—and become distracted and distraught.

There have been so many essays—and entire books!—about burnout.1 Burnout is described this way by Anne Helen Petersen:

“The only way to make it all work is to employ relentless focus—to never, ever stop moving. But at some point, something’s going to give. It’s the student debt, but it’s more. It’s the economic downturn, but it’s more. It’s the lack of good jobs, but it’s more. It’s the overarching feeling that you’re trying to build a solid foundation on quicksand. It’s the feeling, as the sociologist Eric Klinenberg puts it, that “vulnerability is in the air.””2

With the pandemic and its second and third order effects, it’s more yet again. It’s exponentially more.

Just as one crisis subsides, another rears its head, and they are not small squabbles. They run to the very foundations of our social structures—let alone our environmental crisis.

We have, all-at-once, a centuries-long racial justice crisis, a decades-long economic inequality crisis, a decades-long environmental crisis—and newer permutations of old-problems like the social media fueled disinformation crisis, and the latest manifestation of violent Christian extremism.

Within Christianity in America, there’s the specific crises of Christian nationalism (particularly white Christian nationalism), racism, and patriarchy.

It’s all so much, and it’s all so often. We barely have time to know how we feel about things, let alone what we think about them, before we’re expected to have a take worth sharing with our twitter followers or the group text or our partners.

It’s only been a month since the Capitol was stormed by Trump supporters. In that time, Trump was deemed Too Dangerous to Tweet, Biden and Harris were sworn in as President and Vice-President, and both parties continue to vie for power. Republicans make bad-faith appeals to Biden’s calls for “unity” as cover to avoid responsibility for their attempt to undermine the election outcome. I’m still processing that, and I’m sure you might be, too.

Some things can’t wait. Some things just need to be done, and how we feel about them can come later. But those feelings don’t just go away.

It doesn’t help that our inability to acknowledge—let alone process—our emotion is a widespread problem. Various elements of evangelical culture dissuade us from examining our feelings and intuition: we are taught to downplay feelings that make us doubt our faith, to distrust our conscience when it runs contrary to complementarian theology, to question “good” or “bad” feelings that don’t “glorify God.” Anger, particularly white and male anger, is sanctified in the red-faced spitfire sermons we hear; the anger of women is too often discredited. Other emotions are walled off.

Assenting that one has feelings to access is a step that some cis evangelical men (and post-evangelical men, to boot) have trouble getting to. Learning how to process them doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time.

I also think there’s something about getting older at play here, as well. When you’re very young, the world changes with you—you feel closer to it, in a way. Part of getting older (and one hopes, wiser) is to learn to know yourself better, and to know what will take time to process.

It’s all so much. All so often. Work, home life, and the whole world are separated by tabs in your browser—which is to say, they aren’t separate at all.

I think about Marshall McLuhan’s book The Medium is the Massage a lot.

McLuhan was an early media theorist, and this particular book was also turned into an album that’s now available on Spotify:

What’s really surprising about McLuhan’s work is how much it presaged what using the internet feels like, and some of the realities that we navigate and contend with everyday.

This passage was written during the 60s Civil Rights era, when television was forcing the dominant white culture to see the cruelty of Jim Crow. This maxim has been reinforced even further by the power of social media to allow marginalized voices and communities to speak for (and broadcast) themselves. It’s also forced the still-dominant de-facto white culture to begin to understand themselves as being seen racially, as minorities have for their entire history in America.

The following passage elaborates on the pervasive effect of media:

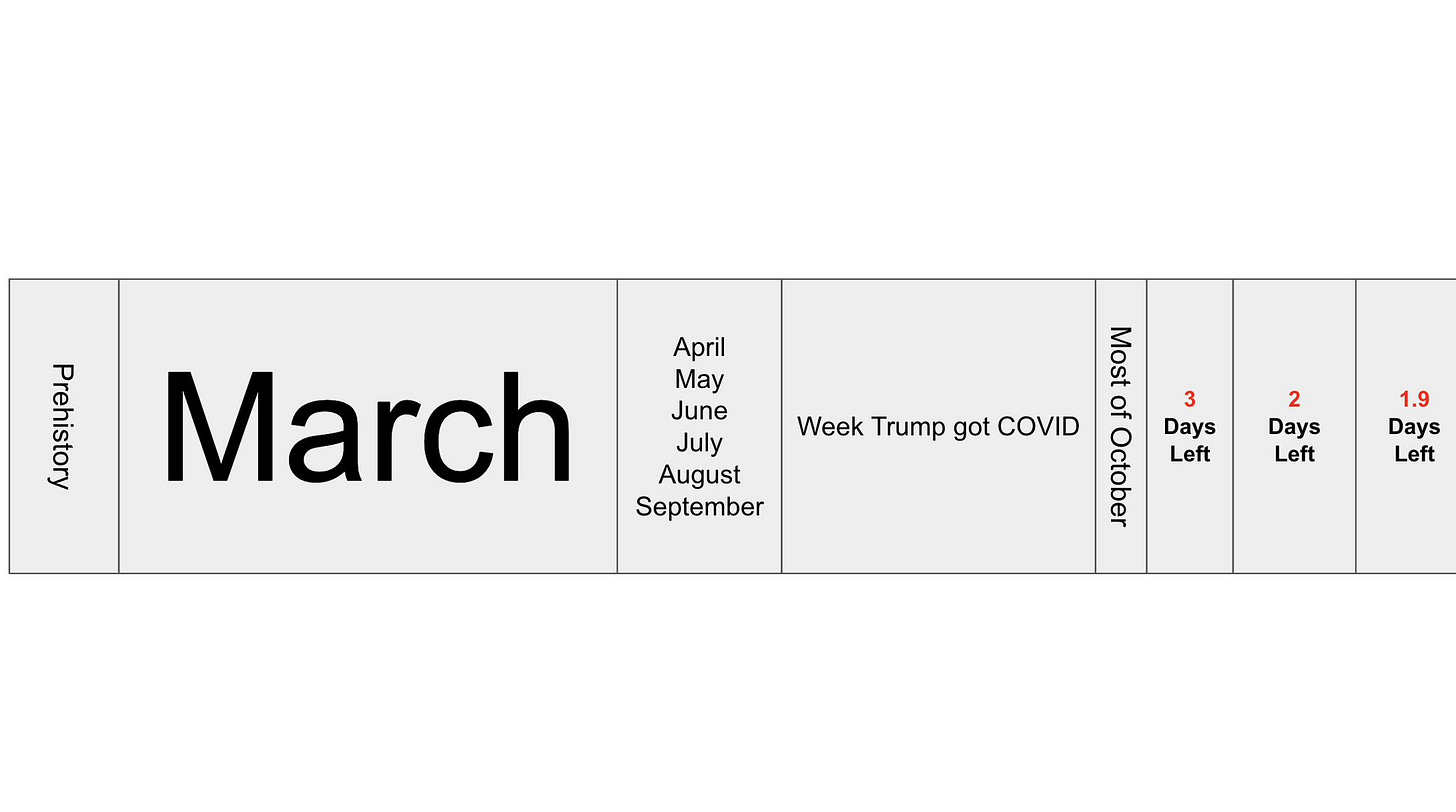

In a locked-down world where nearly everything is mediated, this becomes effect is multiplied. When I think back on just the news of 2020 and early 2021, I can’t hold all of it in my head or recall every thing. It’s why memes like this popped up last year:

All that being said, when we so many are quarantined in our house for nearly a year, watching the news, forcing us to sit and think and feel about all the inequities and injustices on display in our society….it’s all so much. Giving ourselves time to feel, to process, it’s utterly necessary and human. So I’m trying to sit with my feelings more, and not rush through them.

I’ll close with one more McLuhan quotation, and you tell me if it resonates with life in quarantine, mediated through Twitter:

“Ours is a brand-new world of allatonceness. “Time” has ceased, “space” has vanished. We live now in a global village…a simultaneous happening. We are back in acoustic space. We have begun again to structure the primordial feeling, the tribal emotions from which a few centuries of literacy divorced us….electric circuitry profoundly involves men with one another. Information pours upon us, instantaneously and continuously. As soon as information is acquired, it is very rapidly replaced by still newer information...”3

Well, that’s where my head and heart is now, one month on from Jan 6th. Let me know your thoughts by leaving a comment.

If you enjoy this type of philosophizing about media, tech, and being human, be sure to check out my latest episode of Exvangelical with Chris Stedman.

I’ve got some other things in the works that I’m excited to share with you. I just can’t yet. But be sure you’re subscribed!

Ibid.

The Medium is the Massage, by Marshall McLuhan